![[*]](crossref.png) ff).

Therefore

it now needs to be checked

to what extent the functions

ff).

Therefore

it now needs to be checked

to what extent the functions

The motivation of the theory outlined in this appendix was to construct

distribution functions which can play the same role in quantum mechanics

as the conventional phase space probability densities do in classical

mechanics

(cf. pages ![[*]](crossref.png) ff).

Therefore

it now needs to be checked

to what extent the functions

ff).

Therefore

it now needs to be checked

to what extent the functions ![]() actually have the typical properties of probability densities.

actually have the typical properties of probability densities.

A

``genuine''

phase space probability density ![]() is characterized by

the following properties:A.12

is characterized by

the following properties:A.12

The properties (i)-(iii)

are not automatically satisfied for all distribution functions

![]() ,

but must be checked for each individual

,

but must be checked for each individual ![]() .

They are by no means necessary consequences of the definitions in

sections A.1 and A.2.

On the contrary, it can be shown that for nonzero

.

They are by no means necessary consequences of the definitions in

sections A.1 and A.2.

On the contrary, it can be shown that for nonzero ![]() none of the

known

none of the

known ![]() satisfies all three conditions.

This may be interpreted as a consequence

of HEISENBERG's uncertainty relation and was already

observed by WIGNER in 1932 [Wig32].

This shortcoming of all

distribution functions

satisfies all three conditions.

This may be interpreted as a consequence

of HEISENBERG's uncertainty relation and was already

observed by WIGNER in 1932 [Wig32].

This shortcoming of all

distribution functions

![]() is the reason for using the prefix

quasi in terms like quasiprobability density or quasiprobability

distribution function.

is the reason for using the prefix

quasi in terms like quasiprobability density or quasiprobability

distribution function.

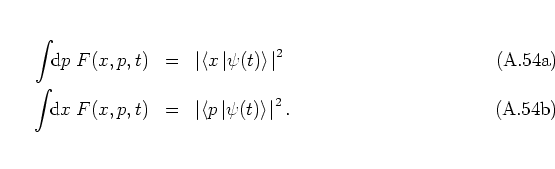

WIGNER's distribution function, for example, is real-valued and gives the

correct

marginal probability distributions for position and momentum,

but it can take on negative values. In fact, it typically oscillates very

rapidly and with large amplitude

between positive and negative values

under variation of ![]() or

or ![]() .

This behaviour of the WIGNER function is

further discussed and demonstrated for some examples

in section

A.6.

.

This behaviour of the WIGNER function is

further discussed and demonstrated for some examples

in section

A.6.

For the antinormal-ordered and the HUSIMI distribution functions one has, using equations

(A.51, A.74),

respectively. Both are real-valued and non-negative. They are even

bounded and do not oscillate as rapidly as ![]() . But, on the

other hand, they do not yield the correct probability densities for

. But, on the

other hand, they do not yield the correct probability densities for ![]() and

and ![]() by

marginalization.

Again I refer the reader to section

A.6 for more details.

Table A.1 gives an overview of the essential properties

of the distribution functions defined in sections A.2

and A.3.

by

marginalization.

Again I refer the reader to section

A.6 for more details.

Table A.1 gives an overview of the essential properties

of the distribution functions defined in sections A.2

and A.3.

It is important to keep in mind that despite the different properties of

the distribution functions, they are all equivalent in the sense that all

of them contain exactly the same information

about

the state of the system.

This can be exploited by choosing that type of distribution

function

![]() (respectively by choosing that kernel function

(respectively by choosing that kernel function ![]() )

that is most suited to study the particular problem in question.

)

that is most suited to study the particular problem in question.

For the purpose of comparing the classical and quantum mechanical

equations of motion of a given system, one usually uses WIGNER's

function (cf. equation (A.82); see [Bun95] for details).

![]() is also especially well suited for the discussion of

scattering systems, because in such systems,

for large energies,

the classical limiting case

often is a good approximation to the exact quantum system already;

equation (A.82) can then be used to

determine

the

quantum

correction terms in a

systematic

way.

On the other hand, if the quantum and classical phase space

(quasi-)

probability densities themselves are in the focus of attention, then most

frequently the HUSIMI distribution function

is also especially well suited for the discussion of

scattering systems, because in such systems,

for large energies,

the classical limiting case

often is a good approximation to the exact quantum system already;

equation (A.82) can then be used to

determine

the

quantum

correction terms in a

systematic

way.

On the other hand, if the quantum and classical phase space

(quasi-)

probability densities themselves are in the focus of attention, then most

frequently the HUSIMI distribution function

![]() or the coherent state representation

or the coherent state representation

![]() are employed.

In section A.6 I discuss some of the advantages of

this choice by considering two familiar quantum states as examples.

are employed.

In section A.6 I discuss some of the advantages of

this choice by considering two familiar quantum states as examples.