In this section I discuss some of the aspects of the practical implementation of the iteration scheme outlined in subsection 2.1.3.

From a formal point of view

the methods

formulating ![]() in

the position representation

(section 3.2)

and the eigenrepresentation of the harmonic oscillator

(subsection 2.1.3 and the present section)

obviously are very similar

-- for example, both equation (2.43) and

equation (3.28)

are

explicit

linear mappings of vectors of complex numbers.

in

the position representation

(section 3.2)

and the eigenrepresentation of the harmonic oscillator

(subsection 2.1.3 and the present section)

obviously are very similar

-- for example, both equation (2.43) and

equation (3.28)

are

explicit

linear mappings of vectors of complex numbers.

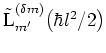

What is more, the dimensions of the matrices ![]() and

and

![]() used for the iterations are of the same order of magnitude, too.

This can be seen as follows.

The dimension

used for the iterations are of the same order of magnitude, too.

This can be seen as follows.

The dimension

![]() to be used for

to be used for

![]() has been

derived in the previous subsection; on the other hand,

the dimension needed for

has been

derived in the previous subsection; on the other hand,

the dimension needed for ![]() is determined by the maximum index

is determined by the maximum index

![]() of the set

of the set

![]() necessary for resolving quantum phase space structures at a distance of

necessary for resolving quantum phase space structures at a distance of

![]() from the origin.

Roughly speaking,

from the origin.

Roughly speaking,

![]() is peaked

around the

corresponding

classical turning points at

is peaked

around the

corresponding

classical turning points at

![]() and decays

exponentially

for larger values of

and decays

exponentially

for larger values of

![]() .3.2This means that, as a rule of the thumb,

the dimension of

.3.2This means that, as a rule of the thumb,

the dimension of ![]() needed for describing the dynamics on the interval

needed for describing the dynamics on the interval

![]() is not very much larger than

is not very much larger than

![]() . This estimate is

close to the value of

. This estimate is

close to the value of

![]() determined in

equation (3.32).

determined in

equation (3.32).

There are some decisive differences between the matrices used for the

two methods, as well.

First of all,

with respect to identical dimensions of the matrices,

storing the matrix elements of ![]() only requires a quarter

of the memory needed for storing the matrix elements of

only requires a quarter

of the memory needed for storing the matrix elements of

![]() :

in practice, the kick matrix elements

:

in practice, the kick matrix elements ![]() of equation (2.51)

-- rather than the

full FLOQUET matrix elements

of equation (2.51)

-- rather than the

full FLOQUET matrix elements ![]() -- are stored in the computer

memory, such that the selection rule

-- are stored in the computer

memory, such that the selection rule ![]() for

for ![]() odd and the

symmetry property

odd and the

symmetry property

![]() can be used

-- see equation (2.51).

Then, each time they are needed during the iteration,

the

can be used

-- see equation (2.51).

Then, each time they are needed during the iteration,

the ![]() are trivially calculated from the

are trivially calculated from the ![]() using the

splitting (2.45).

Storing the

using the

splitting (2.45).

Storing the ![]() requires computer memory for roughly

requires computer memory for roughly

![]() complex numbers, i.e. for the typical value of

complex numbers, i.e. for the typical value of

![]() some 138 MBytes are needed. The

approximate

CPU time per iteration of the quantum map then typically varies

from 45 sec (on a Pentium II with 350 MHz)

to 10 sec (Pentium 4 with 2 GHz).

some 138 MBytes are needed. The

approximate

CPU time per iteration of the quantum map then typically varies

from 45 sec (on a Pentium II with 350 MHz)

to 10 sec (Pentium 4 with 2 GHz).

Second,

in contrast

to the evaluation of (3.30),

computation of the ![]() and thus of the

and thus of the ![]() is a nontrivial

task.

Equation (2.51) shows that the formula

for the

is a nontrivial

task.

Equation (2.51) shows that the formula

for the ![]() is

composed of several terms (BESSEL functions,

generalized LAGUERRE polynomials,

factorials, exponentials) the

absolute values

of which can -- and in practice do

-- differ greatly, such that all kinds of numerical cancellations,

overflows and underflows are to be expected -- and indeed do occur --

when (2.51) is evaluated directly.

Therefore, this calculation has to be implemented in a slightly more

sophisticated way, basically by exploiting the recurrence relation

is

composed of several terms (BESSEL functions,

generalized LAGUERRE polynomials,

factorials, exponentials) the

absolute values

of which can -- and in practice do

-- differ greatly, such that all kinds of numerical cancellations,

overflows and underflows are to be expected -- and indeed do occur --

when (2.51) is evaluated directly.

Therefore, this calculation has to be implemented in a slightly more

sophisticated way, basically by exploiting the recurrence relation

for the generalized LAGUERRE polynomials [AS72].

In this way, not only the abovementioned numerical problems are avoided,

but also the computation of the whole matrix is sped up considerably.

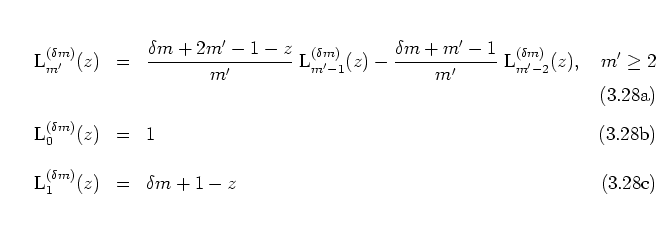

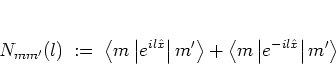

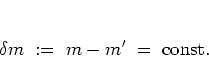

Starting from the kick matrix elements in the form of equation

(2.48) and using the definition

|

(3.28) |

The matrix elements ![]() in this expression need to be studied

with respect to their behaviour along the diagonals given by

in this expression need to be studied

with respect to their behaviour along the diagonals given by

|

(3.30) |

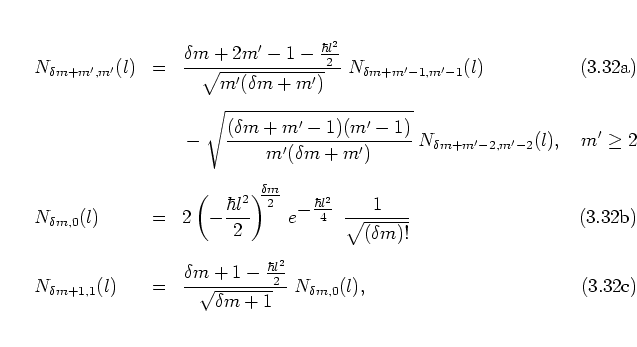

The

![]() can now be calculated efficiently using the

recurrence relation

can now be calculated efficiently using the

recurrence relation

which is obtained by evaluating the

in equation (3.38) by means of the definition

(3.37) and the recursion relation

(3.33) of the generalized LAGUERRE polynomials.

in equation (3.38) by means of the definition

(3.37) and the recursion relation

(3.33) of the generalized LAGUERRE polynomials.

The numerical problems mentioned above with respect to the direct evaluation of equation (2.51) are reduced to a minimum with this algorithm, because multiplying and adding up very large and very small numbers at the same time is avoided here as far as possible: the definition (3.37) avoids the factorials of equation (2.51), and the respective absolute values of the numerators and denominators in each of the fractions in the recursion (3.39a) are constructed to be as comparable as possible.

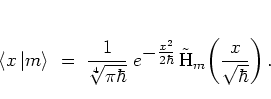

Similarly, when

in the next chapters

![]() needs to be evaluated

numerically

for larger values

of

needs to be evaluated

numerically

for larger values

of ![]() ,

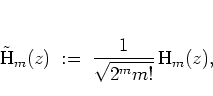

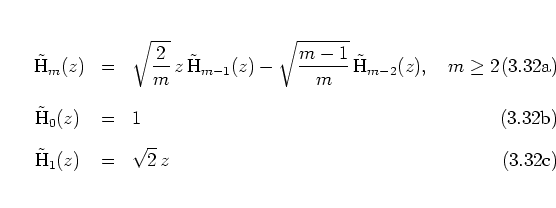

this cannot be done

using

equation (2.39) directly. Rather, a

scaled variant

of the HERMITE polynomials is defined,

,

this cannot be done

using

equation (2.39) directly. Rather, a

scaled variant

of the HERMITE polynomials is defined,

|

(3.32) |

![\begin{subequations}

\begin{eqnarray}

{\mbox{H}}_m(z)

& = & 2z \, {\mbox{H}}_{...

...cm]

{\mbox{H}}_1(z) \hspace*{0.11cm}

& = & 2z

\end{eqnarray}\end{subequations}](img637.png)

|

(3.31) |

With the

![]() computed

as described above,

the series in equation (3.35) can be evaluated term by term.

In the parameter range considered for the numerical calculations

in the following chapters, the series

can

typically be truncated at values of

computed

as described above,

the series in equation (3.35) can be evaluated term by term.

In the parameter range considered for the numerical calculations

in the following chapters, the series

can

typically be truncated at values of ![]() not exceeding 200, while

keeping the error induced by the truncation reasonably small.

(For the maximum relative error due to this truncation,

not exceeding 200, while

keeping the error induced by the truncation reasonably small.

(For the maximum relative error due to this truncation, ![]() was a

somewhat typical value in the practical calculations.)

was a

somewhat typical value in the practical calculations.)

As in the previous sections,

boundary conditions

have to be imposed here, too. After each time step it is checked if the

condition (3.24a) is still satisfied. In practice, for

diffusing states violation of this boundary condition

-- due to the implicit cut-off error as a result of the finite number

![]() of basis elements

of basis elements

![]() used for expanding the states

--

is one of the two main sources of numerical error. The other is the

unavoidable

rounding error

generated in the course of the

numerical

computation

of the

used for expanding the states

--

is one of the two main sources of numerical error. The other is the

unavoidable

rounding error

generated in the course of the

numerical

computation

of the ![]() .

.